In this essay, Br. Ken Homan, SJ reflects on the history of American Jesuit slaveholding in light of his charism. Turning to Ignatius of Loyola's teaching on sin in the Spiritual Exercises, he examines several deflections that can come up in response to this structural sin. Urging a deeper reflection on the depth of the sin and emphasizing that such reflection is never an end in itself, he suggests several ways the First Week of the Spiritual Exercises move a conversation about slaveholding toward greater freedom and justice. Click here to download a copy of this essay.

I sat before the statue of Mary, awkwardly fidgeting and doing my best not to check my watch. Pray about your sinfulness. I wondered what I had gotten myself into and what good would come of these exercises. Sit with Mary and ask to feel abhorrence for your sins. Perceive their disorder. Detest all that is vain. I checked my watch, astounded that only eight minutes of the prescribed hour had gone by. At twenty years old, the First Week of Ignatius of Loyola's Spiritual Exercises was a daunting undertaking.[1] The First Week requires honesty, openness, trust, and humility in a way I had never before experienced. I completed that first attempt at the First Week as best I could; but it has taken me years of annual 8-day retreats to both trust and discover how essential the First Week is.

Ignatius breaks the Exercises into four "weeks" or movements: sin and trusting God's mercy; Jesus's mission; Jesus's passion and crucifixion; and Jesus's resurrection and God's enduring love. These Exercises are undertaken to free ourselves from attachments and open to God's call. In his commentary on the Exercises, Michael Ivens, SJ comments on the First Week: "Mercy, then, is the dominant theme of the First Week Meditations, but there can be no profound sense of God's mercy without a profound sense of one's sin."[2]

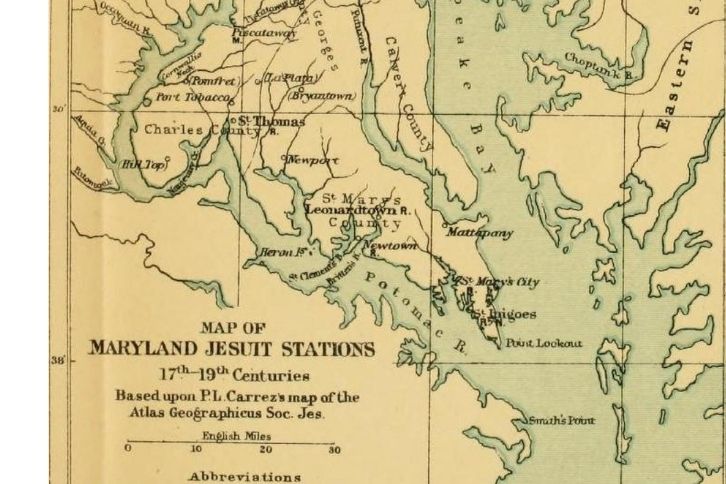

The experience of awkwardness, humility, and demand for openness returned to me this summer. For two weeks, I joined an archeology team at St. Inigoe's, Maryland, the site of one of our former Jesuit plantations. Each day, descendants of those families who we Jesuits had enslaved joined us on the dig. We worked together, speaking at length about the history, reality, and legacy of Jesuit slaveholding. We gathered the broken pieces of pottery, porcelain, pipe stems, bricks, and glass bottles. I listened to the stories, names, feelings, and experiences of those present, all while uncovering artifacts of the lives of those who worked at the plantations.

The time together forced me to ask: Have we American Jesuits honestly engaged with the First Week regarding our slaveholding? Have we had a profound sense of our sinfulness?

Impediments to Honesty

Openly discussing sin can be taboo. Years of overemphasis, misuse, misapplication, and finger-pointing cause many to shirk engagement with the idea of sin, sometimes even rejecting it as a useful category. When I taught high school, a significant portion of my students saw discussions about sin as the prerogative of hypocritical authorities who chastised others but saw themselves as spotless. Many of my young adult Catholic peers feel constantly berated by Church officials regarding sex and beliefs around marriage, ordination, and contraception. On the other hand, other young adult Catholic peers view regular confession as a thriving part of their prayer lives. Among my Jesuit peers, sin and confession are a simple, everyday part of prayer. Despite this, some sinful subjects still seem taboo. Jesuit slaveholding is one of them.

Conversations with my fellow Jesuits about slaveholding vary widely. Discussing racism and the legacy of slaveholding is acceptable in the academic sense. Most applaud the study and research undertaken to learn about the lives of the people we enslaved. When it comes to the legacy of slaveholding and systematic racism, how our schools and institutions continue to benefit from those legacies, and what we owe individuals and communities in reconciliation, the conversations get murkier. Deflections lurk around each corner of the conversation.

Three deflections come up with some regularity.[3] These deflections seek to lessen the burden of confronting sin. They either downplay the sin's significance or try to historicize it in a way that reduces its brutality. I share the deflections here and address their shortcomings briefly thereafter:

It was commonplace.

Slaveholding was increasingly widespread during the years the Jesuits established (and post-Suppression[4] reestablished) themselves in the United States. As with other religious orders, we participated in the full range of slaveholding—buying, selling, renting, borrowing, punishing, and enslaving Black[5] people. When discussing slaveholding, it is common to hear, "Well, nobody was against it at the time: it was commonplace." There is a sense that we should not judge historical actors too harshly for appropriating what was then considered moral.

We also did good.

When discussing slaveholding with my fellow Jesuits, many feel that the discussions of wrongdoing and sin prevent us from acknowledging the good that we did. Whether it was spreading the Gospel or teaching enslaved persons to read and write, there is a sense that emphasis on the sin of slaveholding diminishes a fuller picture. There is a desire for the historical context to affirm the path that we took.

We are trapped by this discussion.

We Jesuits are held to high standards by ourselves, our superiors, our communities, and the Church alike. Indeed, the Church as a whole is held to high standards, as seen by the rightful outrage of the sex abuse crisis. Some feel these standards can be a debilitating trap, that we are not allowed to be human, to struggle, or to question. When it comes to the legacy of slaveholding and our response, there's a temptation to throw one's hands up and frustratedly ask, "What exactly do you want me to do?"

Spiritually (and emotionally), these deflections often emerge from fear and attachments, two conditions Ignatius addresses in the First Week. Fear and attachments impede our ability to honestly wrestle with sin or the legacy of slaveholding. Authentically giving ourselves to the First Week, however, makes us freer and our commitment to justice more fruitful.

Bringing What is Buried to the Light

In the First Week of the Exercises, Ignatius begins with the "Principle and Foundation." It states, "Human beings are created to praise, reverence, and serve God our Lord, and by means of this to save their souls." Ignatius goes on to urge indifference—not to "seek health rather than sickness, wealth rather than poverty, honor rather than dishonor, a longer life rather than a short one, and so on in all other matters."[6] In short, we are to use any possible tools, works, or situations to glorify God.

Sin stands in the way of that glorification.

Ignatius uses the rest of the First Week to help the retreatant honestly place their sins before God. The process is not meant to crush the retreatant under a sense of their own sinfulness. Rather, it is to be open and honest so to recognize the infinite mercy and goodness of God. Ignatius meant for this recognition of God to go beyond the Jesuits or just those who completed the Exercises to extend to all persons, so that all might experience God's tremendous mercy.

That openness begins with a general confession. Ignatius states of the general confession, "During these Spiritual Exercises one reaches a deeper interior understanding of the reality and malice of one's sins than when one is not so concentrated on interior concerns." He points to the role of indifference. Freeing oneself from attachments allows the retreatant to more fully recognize the malevolence of sin. More importantly, it allows the retreatant to recognize the role of God's grace and mercy.

From there, Ignatius turns to the three exercises on sin. In the first, the retreatant asks for shame, confusion, tears, and suffering while praying about the sins of the fallen angels, Adam and Eve, and others in hell. The exercise ends with a colloquy in which the retreatant imagines Christ on the cross. In the second exercise, the retreatant imagines their sins being read off as in a court record, including the time, place, and accomplices. While there is a temptation to linger on the corruption and foulness that Ignatius prescribes, the true movement is toward the wonder at all of God's goodness and mercy. The third exercise is a colloquy, a three-part conversation. The retreatant goes from Mary, to God the Son, to God the Father asking to feel abhorrence for their sins. After repeating the third exercise, the retreatant concludes with a contemplation on Hell—the people there, the smells, the feelings, and the horror of lost souls separated from God.

Upon first glance, these exercises seem to lay a tremendous burden on the retreatant: they ask someone to focus and meditate on the serious and traumatizing nature of sin, without succumbing to hopelessness. The end goal, however, is that recognition of God's mercy and goodness. Having undertaken the Exercises and directed 8-day retreats, I can confidently say that retreatants who bear their sins to God feel a tremendous sense of freedom afterward. That freedom is vital for pursuing justice in a fuller, more authentic manner.

Pursuing that internal and external freedom is frequently difficult. We have many attachments and fears that prevent us from moving forward. I return here to those common deflections and how the First Week might help to move past them.

It was commonplace.

Slaveholding was increasingly commonplace in the United States upon the Jesuits' arrival, and fully cemented at the time of our restoration. To say that nobody was against it, however, is completely false. Enslaved persons regularly fought back against their bondage in a variety of creative ways; to claim otherwise is to disregard the voices of enslaved persons both in the past and at present. Moreover, there were critics in the Church hierarchy as well. In a tweet, Dr. Catherine Addington points out, "if there's one thing you learn from my twitter feed, let it be that "you gotta judge them by the standards of their time" is easily done, because for every chronicle of colonial Spaniards' genocidal actions there's a contemporary who petitioned the Crown to punish their crimes." The same can be said of slaveholding. There were many critics of slaveholding at the time, including in our own Jesuit hierarchy.

This historicization is key—it prevents us from diminishing the sinfulness, forcing the honesty that is pivotal to the First Week. Ignatius suggests in the first exercise that we consider the mortal sin of someone who has gone to hell. As I consider Jesuits and slaveholding, I am forced to ask myself—are there Jesuits in hell because of our slaveholding? I wonder if any of my Jesuit forebearers are like the rich man in Luke 16, desperately wanting to warn our present Company. Being honest about the sinfulness of our slaveholding helps us to heed the prophets, to listen more attentively regarding racial justice in our own time.

We also did good.

No doubt, Jesuits in North America have done a tremendous amount of good. However, Ignatius's teaching in the First Week shows that such good in no way absolves an individual or community from grappling with their sin and the harm they have caused, of which Jesuits are also guilty. If we want to move forward with the Exercises in a full and fruitful way, we must be deeply, shamefully, and painfully sorrowful. That sorrow, however, is not our stopping point. Ignatius makes it abundantly clear that honesty about our sinfulness allows us to truly appreciate the Principle and Foundation and appreciate God's mercy. When we deflect or try to skip ahead, we are in fact shortchanging the goodness and grace God lays before us.

We are trapped by this discussion.

The dynamics of the first week are precisely designed to avoid being trapped by an overwhelming sense of sin. If a deep sense of sin is all the comes from the First Week, the exercise has not been successfully completed. The freedom gained allows us to correctly discern, without attachment, the true and just course of action that God wills for us, including how to handle our sinful history.

The First Week helps to free us from our attachments, fears, and what Ignatius describes as vanity. For myself personally, much of that vanity is about my image as a Jesuit. I want us to be known as the religious order that works tirelessly for justice, that prays deeply, and gives of ourselves to the poor and oppressed. Yet I sometimes attach to that image rather than God who calls us to be those things.

An Ongoing Examen

During the dig, descendants of those families we enslaved regularly pushed me to confront the sins of our historic and present Jesuits alike. We spent hours working alongside each other. While the dig itself was important work, the conversations bore a greater impact on me. Descendants offered several observations and questions that have stood out in my prayer:

- Why are you the only Jesuit here listening to us?

- Is this something Jesuits talk about regularly, or do you avoid it like other uncomfortable topics?

- Is this something you all learn about? Or is it only you making this effort?

- I'm upset that you're the first Jesuit who has made an effort to talk to me.

- Are you actually going to do something about this, or is this dig just an experience?

- I'm just very angry.

- It's just so moving to be in the places my ancestors were, to hear their story, to learn about it. But I'm so hurt that it's taken this long to facilitate a conversation.

- Do you all know what you have done to my family?

These questions and comments gave me pause, forcing me to stop and ask if I had really reckoned with the sins of my own Jesuit brethren; or if I had truly wrestled with the legacy of slaveholding that helped build the Society Jesus in America. I can honestly say that I am in the infancy of that process. The descendants and the dig itself have offered me a prophetic witness and invitation to dig further into Ignatian spirituality. The shattered and scattered pieces of pottery we found on the dig reminded me of the lives we Jesuits likewise shattered and scattered.

As we Jesuits dig further into our slaveholding history, it is equally important that we dig further into the Exercises, particularly the First Week. We might ask ourselves about our present-day attachments and fears. What prevents us from reckoning with our past and pursuing justice for the sins for which our company is responsible? Are we willing, especially with our institutions, to give and not to count the cost? To fight and not to heed the wounds?

Header image: Georgetown Slavery Archive, "Map of Maryland Jesuit Stations, 17th-19th centuries," Georgetown Slavery Archive, https://slaveryarchive.georgetown.edu/items/show/57. Note that St. Inigoe's, where Br. Homan was participating in the archeological dig, is on the map just to the right of the "a" in "Potomac R" on the map.

[1] For those unfamiliar with Ignatius's Spiritual Exercises, a good introduction is Michael Ivens's Understanding the Spiritual Exercises (Herefordshire, England: Gracewing, 1998).

[2] Ivens, Understanding the Spiritual Exercises, 44.

[3] Curiously, they are the same I hear from Jesuits and other Catholics regarding slaveholding, the sex abuse crisis, Native or First Nations residential schools, and sexism in the Church.

[4] In 1773, following pressure from numerous European monarchs, Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Society of Jesus. Several kingdoms (most notably Russia), however, used a loophole to allow the Jesuits to continue ministering and working. In 1814, Pope Pius VII restored the Society. See https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2014/07/22/unlikely-story-how-jesuits-were-suppressed-and-then-restored.

[5] I follow the common practice of capitalizing "Black" as is done with other ethnic identities and following the lead of the National Association of Black Journalists. See this explainer from the David Lanham for more: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/06/16/a-public-letter-to-the-associated-press-listen-to-the-nation-and-capitalize-black/.

[6] See a translation of the "Principle and Foundation" in the context of the entire Exercises by Louis Puhl, SJ, at http://spex.ignatianspirituality.com/SpiritualExercises/Puhl#section_c2n_ypv_b3.